Introduction to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica stands as one of the most powerful anti-war artworks in history. Created in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, the painting was a response to the devastating bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by Nazi and Italian forces allied with Francisco Franco. Commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair, the mural-sized masterpiece became an enduring symbol of the horrors of war and the resilience of the human spirit.

Rendered in stark monochrome, Guernica combines fragmented forms, anguished figures, and symbolic elements to convey its powerful message. While it was initially met with mixed reactions, its global tour transformed it into an icon of political art and a rallying cry for peace. This article explores the historical and artistic dimensions of Guernica, its journey through decades of political turmoil, and its lasting legacy as a universal symbol of protest and hope.

The Spanish Civil War and the Bombing of Guernica

The genesis of Guernica lies in one of the darkest chapters of modern Spanish history: the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). This brutal conflict pitted the Republican government, supported by leftist and anarchist groups, against the Nationalist forces led by General Francisco Franco. The war was not only a domestic struggle but also a precursor to World War II, as it drew international involvement from both fascist and democratic nations.

On April 26, 1937, the small Basque town of Guernica became the target of an unprecedented aerial bombing campaign. Conducted by the German Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion and Italian Aviazione Legionaria, the attack was a strategic move to demoralize Republican forces and support Franco’s Nationalists. The raid resulted in widespread destruction, with fires consuming much of the town and hundreds of civilians losing their lives.

The bombing of Guernica was significant not only for its human cost but also for its symbolic resonance. Guernica was a cultural and historical center of the Basque people, and its destruction represented an attack on their identity and autonomy. Furthermore, it marked one of the earliest instances of deliberate targeting of civilians in modern warfare, signaling a shift in the nature of conflict.

News of the bombing spread rapidly, thanks to reports by journalists such as George Steer, whose vivid descriptions of the carnage shocked the international community. For many, Guernica became a symbol of the growing threat of fascism and the human cost of political and ideological extremism.

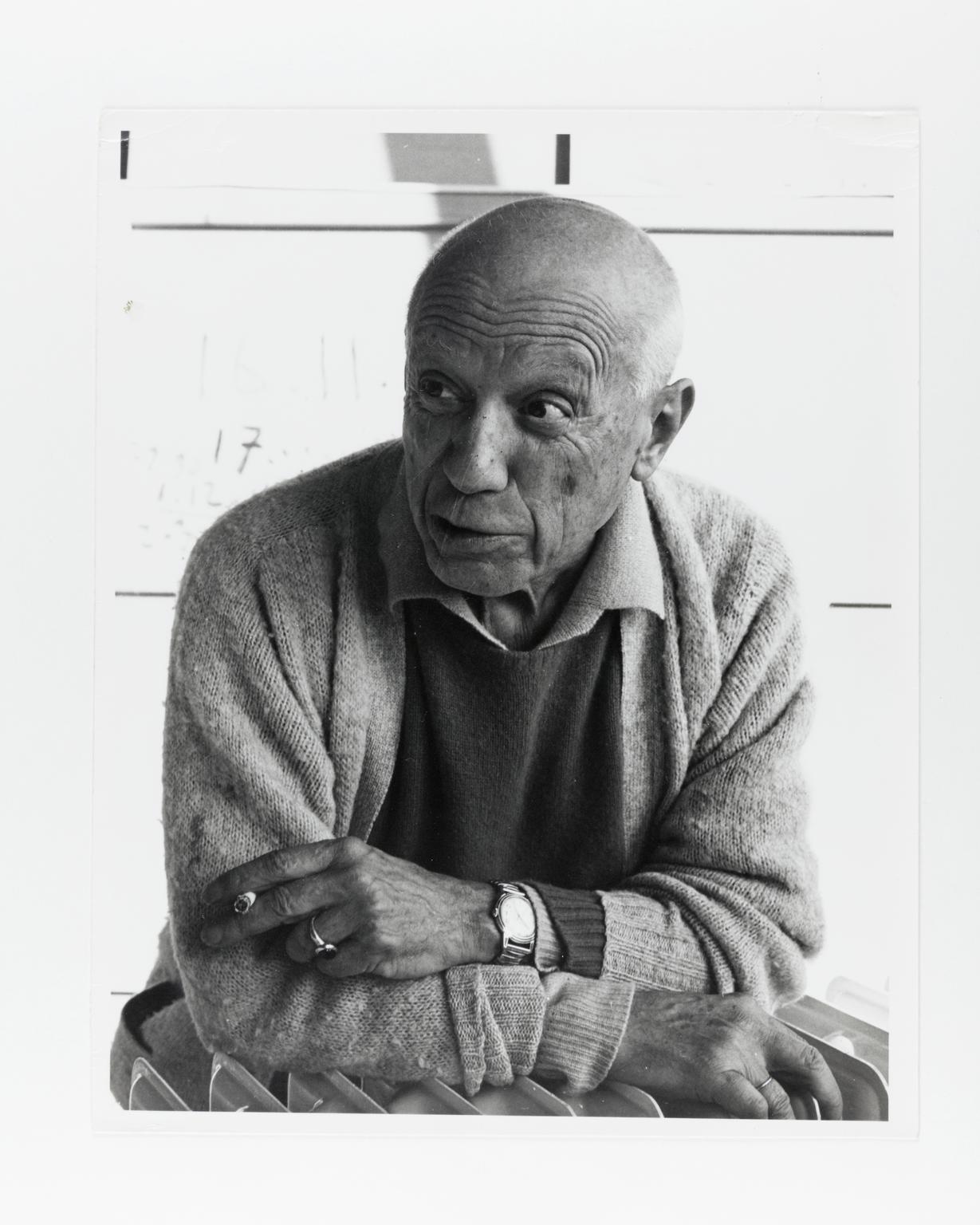

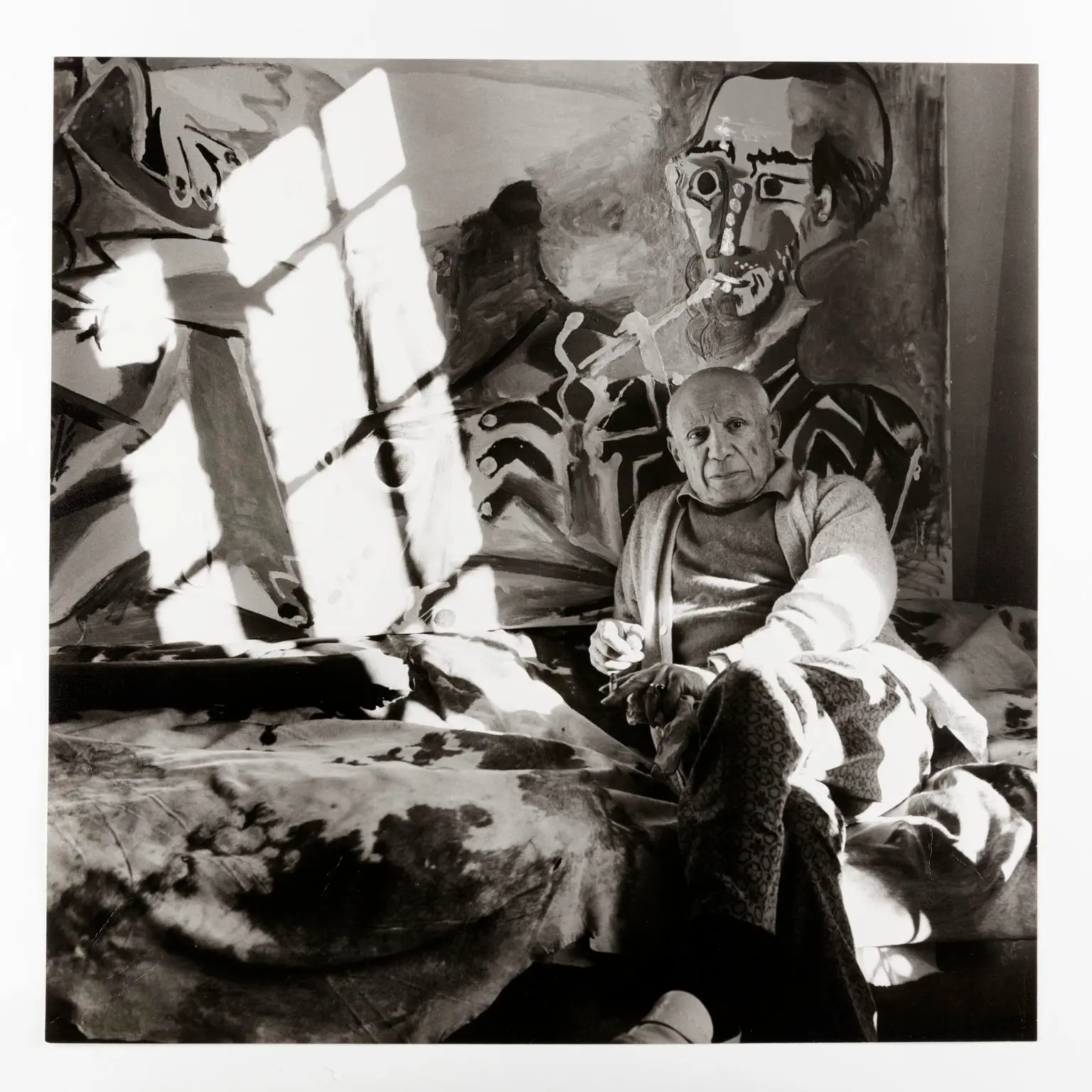

Picasso, a Spaniard living in Paris at the time, was deeply affected by these events. While he had not previously engaged directly with the war in his art, the bombing of Guernica served as a catalyst for his political awakening. The atrocity struck a personal and national chord, compelling him to channel his outrage and grief into what would become one of his most iconic works.

The historical context of Guernica is essential to understanding its profound impact. It was born from a moment of profound crisis, reflecting the fear, chaos, and inhumanity of war. Picasso’s response, however, transformed this tragedy into a universal statement, transcending its immediate circumstances to address broader themes of suffering, resistance, and the resilience of the human spirit.

Commission and Creation: Picasso’s Role in the Paris World’s Fair

The creation of Guernica was rooted in Picasso’s commission for the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. The Spanish Republican government invited Picasso, then one of the most celebrated artists in the world, to produce a large mural for the Spanish Pavilion. The aim was to use art and culture to highlight the Republic’s cause and garner international sympathy amidst the ongoing civil war.

Initially, Picasso struggled to find inspiration for the commission. Despite his deep connection to Spain, his art had largely focused on personal and experimental themes rather than political commentary. However, the bombing of Guernica provided the impetus he needed. The atrocity crystallized his sense of moral obligation, transforming the commission into a personal mission to expose the horrors of war.

Picasso began work on Guernica in May 1937, just weeks after the bombing. Working in his Paris studio, he created a series of preparatory sketches and studies, refining his ideas and experimenting with compositions. These preliminary works reveal Picasso’s process of distilling the chaos and suffering of Guernica into a coherent and impactful visual language.

The painting itself, completed in just over a month, is monumental in scale, measuring 3.5 meters (11 feet) high and 7.8 meters (25.6 feet) wide. Its stark black, white, and gray palette evokes the visual language of newspapers, linking it to the reportage that first brought the bombing to global attention. The monochrome scheme also heightens the emotional intensity of the scene, stripping away distractions to focus on the raw expressions of anguish and destruction.

Picasso’s use of fragmented forms and distorted perspectives reflects the influence of Cubism, a movement he had co-founded decades earlier. This stylistic choice amplifies the sense of chaos and disorientation, mirroring the fragmented lives of the bombing’s victims. Key elements of the composition, such as the screaming woman clutching her dead child, the dismembered soldier, and the anguished horse, convey a visceral sense of human suffering.

The process of creating Guernica was as much about its message as its execution. Picasso’s studio became a space for political discourse, visited by friends, critics, and Republican officials. The painting was not merely an artistic endeavor but also a form of resistance, a bold statement against the forces of fascism and oppression.

When Guernica was unveiled at the Paris World’s Fair, it was met with mixed reactions. While some recognized its profound power and relevance, others found its abstract style challenging or inappropriate for the pavilion’s political message. However, the painting’s subsequent tour across Europe and the Americas cemented its status as a masterpiece of protest art, demonstrating the enduring power of Picasso’s response to one of history’s darkest moments.

The Guernica’s Artistic Process: From Concept to Completion

The artistic process behind Guernica offers a remarkable insight into Pablo Picasso’s genius and his ability to translate complex emotions and historical events into a powerful visual narrative. Spanning just over a month from May to June 1937, the creation of Guernica was an intense, iterative journey that reflected both Picasso’s personal anguish and his desire to capture the universality of human suffering.

Picasso began his work on Guernica shortly after learning about the bombing, drawing initial sketches to experiment with ideas and forms. These preparatory drawings, over 45 in total, reveal the evolution of the composition and the gradual refinement of its symbolic language. Early studies included isolated figures and fragmented animals, with Picasso exploring how best to convey despair, chaos, and resistance.

The painting’s final composition is a carefully orchestrated tableau of anguish and destruction. The central figure of the screaming horse dominates the canvas, its gaping mouth and twisted body encapsulating the agony of war. Surrounding it are other fragmented forms: a woman holding her dead child, a fallen soldier whose hand clutches a broken sword, and a woman with arms outstretched in terror. These figures are set within a space marked by stark light and shadow, evoking the fractured reality of the bombing.

One of the most striking elements of Guernica is its monochromatic palette. Picasso’s decision to use black, white, and shades of gray reflects the somber subject matter and draws parallels to the stark imagery of newspaper photographs. This choice not only enhances the painting’s emotional impact but also underscores its connection to the media reports that first brought the bombing to global attention.

The interplay of light and dark in Guernica is also significant. The glowing light bulb at the top of the canvas, resembling an all-seeing eye, has been interpreted in various ways, from a symbol of technological advancement’s destructive potential to a representation of divine or moral scrutiny. Meanwhile, the sharp, angular beams of light add to the sense of disarray and heighten the dramatic tension.

As Picasso worked on Guernica, he continuously revised its elements, often painting over or reconfiguring figures to enhance their symbolic power. For example, the bull in the upper left corner, a recurring motif in Picasso’s work, evolved from a passive observer to a menacing presence, embodying themes of brutality and resilience. Similarly, the dismembered soldier at the bottom of the canvas became a poignant representation of sacrifice and defiance, his broken sword giving rise to a small flower as a symbol of hope.

The speed with which Picasso completed Guernica is a testament to his urgency and commitment to its message. Working in large-scale dimensions, he combined his mastery of Cubism with a raw emotional intensity, creating a work that transcended its immediate context to become a timeless indictment of war and human suffering.

Picasso’s process was not merely technical but deeply emotional and philosophical, reflecting his belief in art as a means of confronting and challenging the injustices of the world.

Symbolism in Guernica: Decoding Its Elements

The symbolism in Guernica is one of its most compelling features, imbuing the painting with layers of meaning that continue to provoke analysis and debate. Each element of the composition contributes to its powerful critique of war and human suffering, blending personal, cultural, and universal symbols into a cohesive narrative.

One of the most prominent symbols in Guernica is the bull, situated in the upper left corner of the painting. The bull has been interpreted in multiple ways, ranging from a representation of Franco’s fascist regime to a symbol of endurance and resilience. In Spanish culture, the bull is a powerful national icon, and its ambiguous presence in Guernica reflects the complex interplay of destruction and survival within the narrative.

The horse at the center of the composition is another key symbol, its contorted body and anguished expression conveying the terror and pain of the bombing’s victims. Traditionally associated with nobility and strength, the horse’s suffering becomes a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the strongest in the face of violence. Its fragmented appearance, with jagged lines and gaping wounds, mirrors the shattering of lives and communities during the war.

The human figures in Guernica add to its emotional resonance. The woman clutching her dead child is one of the painting’s most harrowing elements, her open-mouthed scream capturing the raw grief and helplessness of loss. This figure has often been compared to religious imagery, such as the Madonna and Child or the Pietà , linking the suffering in Guernica to broader themes of martyrdom and sacrifice.

The dismembered soldier at the bottom of the canvas represents the futility and devastation of war. Despite his broken body, his hand clutches a shattered sword from which a small flower emerges. This juxtaposition of destruction and renewal suggests the possibility of hope and resilience amidst despair.

Another notable symbol is the light bulb, or “eye of the bomb,†positioned near the top of the canvas. This ambiguous element has been interpreted as a representation of technological progress turned destructive or as an all-seeing eye that bears witness to the atrocities of war. Its harsh, artificial glow contrasts with the softer light emanating from the oil lamp held by one of the figures, symbolizing the clash between human warmth and mechanical coldness.

The angular beams and fragmented space in Guernica enhance its symbolic depth. The shattered forms and overlapping perspectives reflect the disorientation and chaos of the bombing, while the absence of color reinforces the starkness of the tragedy. The painting’s overall composition, with its horizontal layout and crowded figures, evokes a sense of claustrophobia and inescapable doom.

Ultimately, the symbolism in Guernica transcends its historical context, making it a universal statement about the horrors of war. By blending specific references with abstract elements, Picasso created a work that speaks to the collective human experience of suffering, resilience, and the longing for peace.

Reception and Impact: The Global response to Picasso’s Guernica

When Guernica was first unveiled at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, it elicited a range of reactions. Its raw emotional power and unconventional style were a stark departure from traditional depictions of war, challenging viewers to engage with its profound message in new ways. Over time, the painting became a defining symbol of anti-war sentiment, its impact transcending its immediate historical context.

At the Paris World’s Fair, the Spanish Pavilion aimed to draw attention to the plight of the Spanish Republic in its fight against Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces. Positioned among other works of art and cultural exhibits, Guernica served as a centerpiece of the pavilion, demanding attention with its monumental scale and striking monochromatic palette. Some viewers were overwhelmed by its intensity, while others struggled to connect with its abstract and fragmented forms. Nonetheless, its ability to provoke strong emotional and intellectual responses was undeniable.

Following its debut, Guernica embarked on a global tour to raise awareness and funds for the Republican cause. It traveled to numerous cities in Europe and the Americas, including London, New York, and Los Angeles. At each stop, the painting became a rallying point for anti-fascist movements, inspiring protests, debates, and discussions about the role of art in addressing political and social issues.

The international reception of Guernica highlighted its dual nature as both a deeply Spanish and universally human work. For Spanish audiences, it symbolized the suffering inflicted by the Civil War and the resilience of the Republican cause. For global audiences, it resonated as a broader indictment of war and violence, capturing the anguish and chaos that transcends national and cultural boundaries.

Critics and commentators lauded Picasso’s ability to convey such complex themes through abstract forms. While some lamented the absence of traditional realism, others recognized that the painting’s fragmented and distorted imagery mirrored the disintegration of human lives and values during times of conflict. Over time, Guernica came to be seen not only as a masterpiece of modern art but also as a powerful political statement.

The painting’s impact extended beyond the art world. It became a symbol of resistance and solidarity for oppressed and marginalized groups worldwide. During the Vietnam War, anti-war activists used Guernica as a visual reference in their protests, emphasizing its continued relevance. Similarly, it has been invoked in discussions about human rights abuses, terrorism, and other atrocities, underscoring its enduring message of empathy and resistance.

Perhaps the most poignant testament to Guernica‘s impact is its role as a cultural and moral touchstone. In 1985, a tapestry reproduction of the painting was installed at the United Nations headquarters in New York, serving as a reminder of the devastating consequences of war. While the original painting remains housed in Madrid’s Museo Reina SofÃa, its legacy continues to inspire artists, activists, and audiences around the globe.

The Guernica’s Journey: From Exile to Return

The physical journey of Guernica reflects its complex relationship with Spain’s history, politics, and cultural identity. For decades, the painting remained in exile, a symbol of resistance against Franco’s regime. Its eventual return to Spain marked a significant moment of reconciliation, reaffirming its place as a national treasure and a universal icon of peace.

After its debut at the Paris World’s Fair, Guernica embarked on a world tour organized by the Spanish Republican government. The painting’s travels were part of an effort to garner support for the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War. However, with Franco’s victory in 1939, the situation changed dramatically. Picasso, a vocal opponent of Franco, declared that Guernica would not return to Spain until democracy was restored.

In 1939, Guernica was shipped to the United States, where it found a temporary home at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. There, it remained for decades, serving as both an artistic landmark and a political statement. Picasso’s insistence on keeping the painting out of Francoist Spain turned it into a powerful symbol of exile and resistance.

During its time at MoMA, Guernica continued to inspire and provoke. The museum displayed it prominently, and it became a focal point for anti-war movements, especially during the Vietnam War. In 1970, a protester defaced the painting with red spray paint, emphasizing its status as a living, contested symbol of political and social struggle.

The painting’s long-awaited return to Spain came in 1981, six years after Franco’s death and the restoration of democracy. After significant negotiations, MoMA transferred Guernica to Spain, where it was initially displayed at the Casón del Buen Retiro in Madrid. This moment marked a turning point in Spain’s reconciliation with its past, as Guernica was embraced not only as a masterpiece of art but also as a symbol of national resilience and renewal.

In 1992, the painting found its permanent home at the Museo Reina SofÃa in Madrid, where it continues to be a centerpiece of the collection. The museum’s careful preservation of Guernica ensures that future generations can engage with its powerful message and historical significance.

The journey of Guernica from exile to return mirrors Spain’s own journey through dictatorship, exile, and eventual democratic restoration. It remains a testament to the enduring power of art to transcend political and temporal boundaries, offering a space for reflection, dialogue, and healing.

Guernica’s Legacy: Influence on Art and political and social movements

Guernica has left an indelible mark on the world, influencing generations of artists, activists, and thinkers. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to address universal themes of suffering, resistance, and the quest for peace.

As a work of art, Guernica has been a source of inspiration for countless creators. Its fragmented forms and emotional intensity have influenced movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism, as well as individual artists like Jackson Pollock and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Beyond its stylistic impact, Guernica has also inspired works that grapple with political and social issues, affirming the power of art as a medium for activism and protest.

The painting’s legacy extends beyond the realm of art. It has become a symbol of resistance for social movements worldwide, from anti-war demonstrations to campaigns for human rights and environmental justice. Its stark imagery and moral weight make it a potent tool for advocacy, reminding audiences of the human cost of violence and the importance of solidarity.

Guernica‘s role as a global icon was reinforced by its reproduction as a tapestry at the United Nations. Installed in 1985, this reproduction has served as a backdrop for discussions on peace and conflict, reminding world leaders of their responsibility to prevent atrocities. The tapestry’s temporary removal in 2003 during a press conference about the Iraq War sparked controversy, highlighting the painting’s continued relevance in contemporary politics.

The painting’s enduring power lies in its ability to transcend its original context. While it was created in response to a specific historical event, its themes resonate across cultures and eras, making it a universal statement about the human condition.

Conclusion

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is more than a masterpiece; it is a timeless symbol of the horrors of war and the resilience of the human spirit. Born from the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War, the painting transcends its historical origins to address universal themes of suffering, resistance, and hope.

Through its powerful symbolism and emotional intensity, Guernica has inspired generations of artists, activists, and thinkers. Its global journey, from its creation in Paris to its eventual return to Madrid, reflects its enduring significance as both a national treasure and a universal icon.

Today, Guernica continues to provoke dialogue and reflection, reminding us of the devastating consequences of conflict and the importance of striving for peace. As a work of art and a political statement, it stands as a testament to the transformative power of creativity in confronting and challenging injustice.